By Jennifer Jenkins, Director of Duke’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain

January 1, 2023 is Public Domain Day: Works from 1927 are open to all!

On January 1, 2023, copyrighted works from 1927 will enter the US public domain. 1 They will be free for all to copy, share, and build upon. These include Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse and the final Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle, the German science-fiction film Metropolis and Alfred Hitchcock’s first thriller, compositions by Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller, and a novelty song about ice cream. Please note that this site is only about US law; the copyright terms in other countries are different.

Here are just a few of the works that will be in the US public domain in 2023. 2 They were supposed to go into the public domain in 2003, after being copyrighted for 75 years. But before this could happen, Congress hit a 20-year pause button and extended their copyright term to 95 years. Now the wait is over. (To find more material from 1927, you can visit the Catalogue of Copyright Entries.)

Books

- Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

- Arthur Conan Doyle, The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes

- Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop

- Countee Cullen, Copper Sun

- A. A. Milne, Now We Are Six, illustrations by E. H. Shepard

- Thornton Wilder, The Bridge of San Luis Rey

- Ernest Hemingway, Men Without Women (collection of short stories)

- William Faulkner, Mosquitoes

- Agatha Christie, The Big Four

- Edith Wharton, Twilight Sleep

- Herbert Asbury, The Gangs of New York (the original 1927 publication)

- Franklin W. Dixon (pseudonym), The Tower Treasure (the first Hardy Boys book)

- Hermann Hesse, Der Steppenwolf (in the original German)

- Franz Kafka, Amerika (in the original German)

- Marcel Proust, Le Temps retrouvé (the final installment of In Search of Lost Time, in the original French)

These are just a handful of the thousands of books entering the public domain in 2023. There is a lot to celebrate: a modernist masterpiece, poetry from the Harlem Renaissance, children’s verses featuring Winnie-the-Pooh and other characters, and early works from Hemingway and Faulkner. Copyright will also expire over Arthur Conan Doyle’s final Sherlock Holmes stories—you can read more about copyright over characters and the Doyle estate’s attempts to artificially extend rights over Holmes and Dr. Watson here.

Movies Entering the Public Domain

- Metropolis (directed by Fritz Lang)

- The Jazz Singer (the first feature-length film with synchronized dialogue; directed by Alan Crosland)

- Wings (winner of the first Academy Award for outstanding picture; directed by William A. Wellman)

- Sunrise (directed by F.W. Murnau)

- The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (Alfred Hitchcock’s first thriller)

- The King of Kings (directed by Cecil B. DeMille)

- London After Midnight (now a lost film; directed by Tod Browning)

- The Way of All Flesh (now a lost film; directed by Victor Fleming)

- 7th Heaven (inspired the ending of the 2016 film La La Land; directed by Frank Borzage)

- The Kid Brother (starring Harold Lloyd; directed by Ted Wilde)

- The Battle of the Century (starring the comedy duo Laurel and Hardy; directed by Clyde Bruckman)

- Upstream (directed by John Ford)

1927 marked the beginning of the end of the silent film era, with the release of the first full-length feature with synchronized dialogue and sound. Here are the first words spoken in a feature film from The Jazz Singer: “Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain’t heard nothing yet.” Read about the transition from the silent film to the “talkie” era, and the quest to preserve some of the remarkable silent films on this list, here. Please note that while the original footage from these films will be in the public domain, newly added material such as musical accompaniment might still be copyrighted. If a film has been restored or reconstructed, only original and creative additions are eligible for copyright; if a restoration faithfully mimics the preexisting film, it does not contain newly copyrightable material. (Putting skill, labor, and money into a project is not enough to qualify it for copyright. The Supreme Court has made clear that “the sine qua non of copyright is originality.”) In the list above, while some of the titles were not registered for copyright until 1928 or 1929, the original version of the film was published with a 1927 copyright notice, so the copyright expires over that version in 2023.

Musical Compositions

- The Best Things in Life Are Free (George Gard De Sylva, Lew Brown, Ray Henderson; from the musical Good News)

- (I Scream You Scream, We All Scream for) Ice Cream (Howard Johnson, Billy Moll, Robert A. King)

- Puttin’ on the Ritz (Irving Berlin)

- Funny Face and ’S Wonderful (Ira and George Gershwin; from the musical Funny Face)

- Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man and Ol’ Man River (Oscar Hammerstein II, Jerome Kern; from the musical Show Boat)

- Back Water Blues, Preaching the Blues, Foolish Man Blues (Bessie Smith)

- Potato Head Blues, Gully Low Blues (Louis Armstrong)

- Rusty Pail Blues, Sloppy Water Blues, Soothin’ Syrup Stomp (Thomas Waller)

- Black and Tan Fantasy and East St. Louis Toodle-O (Bub Miley, Duke Ellington)

- Billy Goat Stomp, Hyena Stomp, Jungle Blues (Ferdinand Joseph Morton)

- My Blue Heaven (George Whiting, Walter Donaldson)

- Diane (Erno Rapee, Lew Pollack)

- Mississippi Mud (Harry Barris, James Cavanaugh)

works include a song about ice cream and

a film with the Guinness record for the

most pies thrown (3,000). A la mode, please!

This year’s musical line-up includes Broadway hits, early blues songs, jazz standards, and more. Only the musical compositions—the music and lyrics that you might see on a piece of sheet music—are entering the public domain, not the recordings of those songs, which are covered by a separate copyright. Irving Berlin’s words and music to Puttin’ on the Ritz were registered for copyright in 1927 and are now free for anyone to copy, perform, record, adapt, or interpolate into their own song. But the 1930 recordings by Harry Richman and by Fred Astaire are still copyrighted. Note, however, that sound recording rights are more limited than composition rights—you can legally imitate a sound recording, even if your imitation sounds exactly the same, you just cannot copy from the actual recording.

Last year, decades of sound recordings made from the advent of recording technology through the end of 1922 went into the public domain. This year no sound recordings are entering the public domain—for that, we will have to wait until January 1, 2024, when recordings from 1923 will become open for legal reuse. 3

Keep reading to learn more about the public domain! You can use the links below to jump to different sections of this article.

- “The Best Things in Life are Free”

- The Law

- Sherlock Holmes and the Adventure of the Public Domain Character

- Saving silent films

- The Tip of the (Melting) Iceberg

- Oh NO, Canada!

- Born in the Public Domain

- Conclusion

“The Best Things in Life are Free”

outside of ourselves, to know what another

sees of a universe which is not the same

as ours, and whose landscapes would

otherwise have remained as unknown

to us as those of the moon.

–Marcel Proust, Le Temps Retrouvé

(My translation from the original French)

This is the title of one of the songs entering the public domain in 2023. It’s certainly appropriate for Public Domain Day.

Why celebrate the public domain? When works go into the public domain, they can legally be shared, without permission or fee. Community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can perform the music publicly, without paying licensing fees. Online repositories such as the Internet Archive, HathiTrust, Google Books, and the New York Public Library can make works fully available online. This helps enable access to cultural materials that might otherwise be lost to history. 1927 was a long time ago. The vast majority of works from 1927 are out of circulation. When they enter the public domain in 2023, anyone can rescue them from obscurity and make them available, where we can all discover, enjoy, and breathe new life into them.

The public domain is also a wellspring for creativity. The whole point of copyright is to promote creativity, and the public domain plays a central role in doing so. Copyright law gives authors important rights that encourage creativity and distribution—this is a very good thing. But it also ensures that those rights last for a “limited time,” so that when they expire, works go into the public domain, where future authors can legally build on the past—reimagining the books, making them into films, adapting the songs and movies. That’s a good thing too! Think of all the films, cartoons, video games, books, plays, and other works based on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) or Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (1865). As explained in a New York Times editorial: “When a work enters the public domain it means the public can afford to use it freely, to give it new currency . . . [public domain works] are an essential part of every artist’s sustenance, of every person’s sustenance.”

Karyn A. Temple, former United States Register of Copyrights, described the public domain as “part of copyright’s lifecycle, the next stage of life for that creative work. The public domain is an inherent and integral part of the copyright system. . . . It provides authors the inspiration and raw material to create something new.”

Just as Shakespeare’s works have given us everything from 10 Things I Hate About You and Kiss Me Kate (from The Taming of the Shrew) to West Side Story (from Romeo and Juliet), who knows what the works entering the public domain in 2023 might inspire? As with Shakespeare, the ability to freely reinvent these works may spur a range of creativity, from the serious to the whimsical, and in doing so allow the original artists’ legacies to endure. And of course Shakespeare himself, who predated copyright law, borrowed heavily from his predecessors. One work inspires another. That is how the public domain feeds creativity.

After F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) entered the public domain in 2021, The New York Times reported a wealth of new editions with introductions by the likes of Times critic and Pulitzer-Prize winner Wesley Morris and Harvard scholar David J. Alworth, bringing “fresh analysis, nearly a century later, of what our ideas of ‘American’ now entail.” There were also new works such as Michael Farris Smith’s prequel Nick, which tells the backstory of Nick Carraway, a graphic novel adaptation, The Gay Gatsby, The Great Gatsby Undead (the zombie edition), and reports of an animated movie as well as a Gatsby musical by Florence Welch from Florence + the Machine. The hosts of Planet Money even created an audio book, reading the entire book on the air.

Last year’s entry of Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) into the public domain likewise sparked a range of creativity. The most publicity went to celebrity and incongruous reuses, from Ryan Reynolds’ “Winnie-the-Screwed” ad for Mint Mobile to a comic strip in which Pooh celebrates his nudity to the horror film Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey. In my inbox are cuddlier drawings and poems such as this that did not generate as much buzz, but do reflect how Pooh inspired artists and writers on a smaller scale. Are all of these new works critically acclaimed or something rights holders would approve of? No. But they are still part of our culture, and time will tell whether they will be rewarded in the marketplace or have enduring appeal. And, just as Pride and Prejudice and Zombies did not diminish the luster of Jane Austin’s novel (at least for me), the original Winnie-the-Pooh remains intact.

This year’s works offer a temporal cross section of our cultural past, capturing the era in its complexity—the good, the bad, and the ugly. They range from stunning and thought-provoking, to adorable and humorous, to racist and disturbing. In 1927 the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing, but there was also legally-enforced segregation, and many works from the era contain racial slurs and demeaning stereotypes. 4 When such works enter the public domain, anyone is free to grapple with and reimagine them, including in a corrective way. The public domain is a repository of our history—a record of all of our culture, not just the parts we like. Indeed, it is precisely because the works are no longer subject to control by their copyright holders that both their beauty and their ugliness can be freely explored by today’s scholars and citizens; the owner can no longer insist on presenting only a bowdlerized, cleaned-up version that hides important aspects of the original.

For those who want to learn more about US copyright law, here are some important basics.

- Our featured works are only entering the public domain under US copyright law, where works published before 1978 are public domain on January 1 the year after the conclusion of a 95-year copyright term, so long as they complied with copyright’s notice and renewal requirements. Doing the math, works from 1927 were copyrighted for 95 years—through 2022—and are in the public domain January 1 2023. The terms in other countries are different. If you are in the US, Der Steppenwolf and Le Temps Retrouvé entered the public domain in 2023. But in the EU, where the term for those works lasts 70 years after the author’s death, Hermann Hesse’s (1877-1962) works are still copyrighted while Marcel Proust’s (1871-1922) works are in the public domain (they came out of copyright a long time ago before the EU extended its term). In the US, works created since 1978 also have the life-plus-70 term, unless they are works of corporate authorship, which are copyrighted for 95 years after publication. (Believe it or not, this is a simplified explanation of copyright terms—more information can be found on this excellent chart on Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States.)

- For all of the works listed above, only the original works published in 1927 are entering the US public domain. Later versions of them—adaptations, movies, or translations—may still be copyrighted. However, those copyrights only cover newly added creative material. The original content from the 1927 book remains free. So the version of Herbert Asbury’s The Gangs of New York published in 1927 is in the public domain, but new material in subsequent versions, translations into other languages, and Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film are still copyrighted.

- In the US, only the author’s works from 1927 and earlier are in the public domain, not all of the other work published by that author. While you are free to use Hemingway’s short stories in Men without Women (including Hills Like White Elephants and In Another Country), later books such as A Farewell to Arms (1929) and For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) are still copyrighted.

As you can see, copyright is unduly complex, and determining whether older works are in the public domain can be an exercise in detective work. The registration and renewal records in the Catalogue of Copyright Entries (CCE) provide a useful starting point—we spend months combing through this data. But sometimes the dates in the CCE do not match the original publication date that is used for calculating the copyright term, and sometimes there are multiple entries for different versions of the same title. In the CCE, The Battle of the Century and The Gangs of New York show a 1928 registration and Wings shows a 1929 date (perhaps for a version of the film with a musical score added). On actual copies of those works, however, there is a copyright notice reading 1927 or MCMXXVII, meaning that the original versions of those works are in the public domain in 2023 (or perhaps earlier if the renewal was not timely). 5 Puttin’ on the Ritz was in a different situation—its registration was in 1927 even though it was not published until later, and under the law the active date is the 1927 registration date. Finally foreign works such as Metropolis and The Lodger are copyrighted through 2022 because of a provision that, in 1996, restored copyright over certain foreign works that were in the public domain because of non-compliance with notice or renewal requirements. For additional guidance from the Copyright Office, see its circulars on Duration of Copyright, How to Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work, and Copyright Restoration Under the URAA. The footnotes to this article also contain more information.

As you can see, copyright is unduly complex, and determining whether older works are in the public domain can be an exercise in detective work. The registration and renewal records in the Catalogue of Copyright Entries (CCE) provide a useful starting point—we spend months combing through this data. But sometimes the dates in the CCE do not match the original publication date that is used for calculating the copyright term, and sometimes there are multiple entries for different versions of the same title. In the CCE, The Battle of the Century and The Gangs of New York show a 1928 registration and Wings shows a 1929 date (perhaps for a version of the film with a musical score added). On actual copies of those works, however, there is a copyright notice reading 1927 or MCMXXVII, meaning that the original versions of those works are in the public domain in 2023 (or perhaps earlier if the renewal was not timely). 5 Puttin’ on the Ritz was in a different situation—its registration was in 1927 even though it was not published until later, and under the law the active date is the 1927 registration date. Finally foreign works such as Metropolis and The Lodger are copyrighted through 2022 because of a provision that, in 1996, restored copyright over certain foreign works that were in the public domain because of non-compliance with notice or renewal requirements. For additional guidance from the Copyright Office, see its circulars on Duration of Copyright, How to Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work, and Copyright Restoration Under the URAA. The footnotes to this article also contain more information.

Sherlock Holmes and the Adventure of the Public Domain Character

What happens when a work containing a character such as Sherlock Holmes enters the public domain, but that character also appears in still-copyrighted works? The law is clear that the original version of the character enters the public domain at the same time as the work that contained it, even if subsequent installments or episodes are still under copyright. But not every rights owner likes that answer! This was an important issue last year when the original Winnie-the-Pooh entered the public domain. It will be front and center next year when the first appearance of Mickey Mouse goes into the public domain. And it is a theme this year because in 2023 the copyright will finally expire over The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes, which contains the last two Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. For years the Doyle estate has tried to prolong copyright over the characters of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. Now its character-copyright game is up.

The ingenious detective and his faithful sidekick have actually been in the public domain for a long time. They were first introduced in 1887 and were featured in at least fifty stories that came out of copyright before Congress extended the copyright term in 1998. But that did not stop Conan Doyle Estate Ltd. from demanding licensing fees, based on the characters’ reappearance in a handful of later stories that were still under copyright. Most people simply paid up. The estate even has a website boasting about its licensing deals. But Leslie Klinger, a lawyer and Sherlock Holmes scholar, fought back.

Klinger was the co-editor of In the Company of Sherlock Holmes, an anthology of new Sherlock Holmes stories inspired by Doyle’s works. The Doyle estate threatened to block the book’s distribution, telling the publisher: “do not expect to see it offered for sale by Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and similar retailers. We work with those compan[ies] routinely to weed out unlicensed uses of Sherlock Holmes from their offerings, and will not hesitate to do so with your book as well.”

Klinger went to court to seek a declaratory judgment in court that he was free to use the Holmes and Watson characters from Doyle’s public domain works. In response, the Doyle estate presented a bizarre legal theory that a “character is a work of authorship separate from the stories” so that the copyright term for characters does not commence until “the creation of the characters [is] complete.” By this logic, because Sherlock Holmes’ character development continued in stories that were still under copyright, his entire character—including all of the core aspects fully developed in earlier stories—was still copyrighted. This would have created a special end-run around the public domain for characters, who would remain copyrighted so long as their owners keep tweaking them in subsequent works, potentially forever.

“It is a bedrock principle of copyright that once work enters the public domain it cannot be appropriated as private (intellectual) property, and even the most creative of legal theories cannot trump this tenet.” –Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate (N.D. Ill. 2013)

In December 2013, a court decisively rejected this theory and confirmed that all of the elements in the out-of-copyright Sherlock Holmes stories are “free for public use.” It explained: “Where an author has used the same character in a series of works, some of which are in the public domain, the public is free to copy story elements from the public domain works.”

The estate appealed, in a move that the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals described as bordering on the “frivolous” and “quixotic.” The appeals court affirmed Klinger’s right to use the Holmes and Watson characters and awarded him attorney’s fees. Judge Richard Posner called out the estate’s “unlawful business strategy”:

The Doyle estate’s business strategy is plain: charge a modest license fee for which there is no legal basis, in the hope that the ‘rational’ writer or publisher asked for the fee will pay it rather than incur a greater cost, in legal expenses, in challenging the legality of the demand…only Klinger (so far as we know) resisted. In effect he was a private attorney general, combating a disreputable business practice — a form of extortion…It’s time the estate, in its own self-interest, changed its business model. Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate (7th Cir. 2014)

Instead of changing its business model, however, the Doyle estate mounted another “curious” copyright claim in 2020, this time against the Enola Holmes Mysteries books and Netflix’s first Enola Holmes movie. It acknowledged that anyone is “free to use and adapt the characters” in the public domain Sherlock Holmes stories. Its new theory was that it had a copyright in certain personality traits that Holmes exhibited in later, still-copyrighted stories, where he “became capable of friendship,” began to “express emotion” and “respect women,” and even developed a “great interest” in dogs. This theory did not succeed. It is “elementary” copyright doctrine that generic traits such as warmth, empathy, respect, and canine enthusiasm are unprotectable ideas. 6 The parties agreed to dismiss the lawsuit and settled in December 2020.

As of 2023, all of Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes works will be in the public domain. There will no longer be any mystery about whether Klinger, Netflix, or anyone else can use Holmes and Watson. The estate’s unsuccessful attempts to artificially extend their copyrights until this milestone illustrate two key legal points.

- First, under US copyright law, anyone is free to use a character as it has been developed in public domain works, whether it is Winnie-the-Pooh, Sherlock Holmes, or Mickey Mouse (next year). If that character recurs in later works that are still under copyright, the rights only extend to the newly added material in those works, not the underlying material from the public domain works—that content remains freely available.

- Second, not all of the newly added material in the later works is copyrightable. In order to qualify for copyright, it must be “original, creative expression,” meaning that it was independently created (as opposed to copied from somewhere else) and possesses at least a modicum of creativity. Mere “ideas” such as generic character traits are not copyrightable. Nor are “merely trivial” variations added to the original character. In addition, using commonplace elements that have become standard or indispensable (copyright law calls these “scènes à faire”) is not infringement.

For more information, including the interaction between expired copyrights and a different set of rules under trademark law, you can read our analysis of Winnie-the-Pooh and copyright and trademark claims over public domain characters here.

Saving silent films

1927 was a transitional year for cinema. The release of The Jazz Singer—the first feature-length “talkie” with (brief) synchronized dialogue, along with singing and sound effects—ushered in the beginning of the end of the silent film era. Unfortunately, the film also shows performances in blackface, a distressing reminder of the racist stereotypes that dominated portrayals of African-Americans in popular culture.

Most of the films on our list are from the last hurrah of silent features. Many were pathbreaking works of art that influenced generations to come. Wings set the standard for aerial combat footage, from World War II movies to Top Gun. Its director, William Wellman, had himself been a decorated fighter pilot in World War I, and over 300 pilots helped to create the realistic dogfight scenes. (You can read more Wellman and the film’s production in this book by Wellman’s son.) Metropolis laid the cinematic groundwork for many familiar movies. Here is how Roger Ebert described its impact and progeny:

Generally considered the first great science-fiction film, “Metropolis” (1927) fixed for the rest of the century the image of a futuristic city as a hell of scientific progress and human despair. From this film, in various ways, descended not only “Dark City” but “Blade Runner,” “The Fifth Element,” “Alphaville,” “Escape From L.A.,” “Gattaca,” and Batman’s Gotham City. The laboratory of its evil genius, Rotwang, created the visual look of mad scientists for decades to come, especially after it was mirrored in “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935). And the device of the “false Maria,” the robot who looks like a human being, inspired the “Replicants” of “Blade Runner.” Even Rotwang’s artificial hand was given homage in “Dr. Strangelove.”

As incredible as such films are to watch, it is equally incredible that we are able to watch them at all. The rise of sound films precipitated the demise of silent films. Studios (wrongly) believed that their silent film libraries no longer had commercial or cultural value. Tragically, films were destroyed or discarded to clear up storage space or melted down for the silver contained in their substrate. Films that were not destroyed were allowed to decay. The cellulose nitrate base of these older films was prone to shrinkage, outgassing, even spontaneous combustion, and many works have deteriorated beyond repair. In 2013 David Pierce issued an in-depth Library of Congress study called The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929. In the Foreword, the Librarian of Congress James H. Billington summed up its finding that 75% of American silent films are lost to history in their complete form:

The Library of Congress can now authoritatively report that the loss of American silent-era feature films constitutes an alarming and irretrievable loss to our nation’s cultural record. Even if we could preserve all the silent-era films known to exist today in the U.S. and in foreign film archives—something not yet accomplished—it is certain that we and future generations have already lost 75% of the creative record from the era that brought American movies to the pinnacle of world cinematic achievement in the twentieth century.

The long copyright term has contributed to the loss of our cinematic heritage. 7 One of the most important stated goals of copyright term extension was to preserve access to our culture. Instead, old films have disintegrated, rotting in their cans, while preservationists eagerly waited for them to enter the public domain so that they could legally digitize them. (There is a narrow provision in the law allowing for some restorations, but it is limited and does not safeguard the work of many preservationists. You can read our analysis of how long copyright terms thwart film preservation efforts here.) The Library of Congress report confirms: “The public domain status of some films has encouraged their survival,” referring to films that came out of copyright because the rights were not renewed, which allowed others to invest in their preservation.

lost film London After Midnight

A search in the Library of Congress’ silent film database indicates that two of the features on our list—London After Midnight and The Way of All Flesh—are likely to be lost forever. Only still photographs shot during filming remain for London After Midnight, and only fragments remain for The Way of All Flesh.

Other films on the list have only been restored through dedication, serendipity, and a lot of money. Most of director John Ford’s silent films are lost, but in 2009, Upstream was discovered in New Zealand. Wings was also long forgotten and feared lost. As reported in the Los Angeles Times, “The original nitrate negative and early material had long disappeared, so Paramount searched the world for the best remaining elements, finally finding the most comprehensive print — a duplicate negative made from a nitrate print in the late 1950s — in its own vaults.” In 2012, Paramount restored the film for the studio’s 100th anniversary. No one knows who made that duplicate negative; Andrea Kalas, Vice President of Archives at Paramount, told Forbes, “whoever it was, thank you very much, in the late 1950s, for saving this film.” Unfortunately Kalas also suggested at the San Francisco silent film festival that the expensive restoration—a $700,000 investment—was unlikely to be recouped.

The original, longer cut of Metropolis was considered lost until relatively recently, to the dismay of film historians and enthusiasts. Then in 2008 a copy with the missing scenes was found in the archives of the Museo del Cine in Argentina in 2008. Another was found in the National Film Archive of New Zealand. These discoveries allowed most—but not all—of the original to be reassembled in The Complete Metropolis (2010). Some of the original footage was damaged beyond repair; those scenes were replaced with title cards. Celebrating the reconstructed film, Larry Rohter wrote in The New York Times:

For fans and scholars of the silent-film era, the search for a copy of the original version of Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” has become a sort of holy grail. One of the most celebrated movies in cinema history, “Metropolis” had not been viewed at its full length roughly two and a half hours since shortly after its premiere in Berlin in 1927…for the first time, Lang’s vision of a technologically advanced, socially stratified urban dystopia, which has influenced contemporary films like “Blade Runner” and “Star Wars,” seems complete and comprehensible.

As is often the case, the story of Metropolis has a copyright wrinkle. The Complete Metropolis has its own copyright but, as reflected in its copyright registration, this copyright only covers newly added “English Intertitles” (title cards). The pre-existing silent footage and original intertitles from 1927 are out of copyright. And this is actually the second time that Metropolis has gone into the US public domain. The first was in 1955, when its initial 28-year term expired and the rights holders did not renew the copyright. Then in 1996 a new law restored the copyrights in qualifying foreign works. Metropolis, along with thousands of other works, was pulled out of the public domain, and now reenters it after the expiration of the 95-year term, with the once missing scenes available for anyone to reuse.

From a futuristic dystopia in we turn to another, more light-hearted “holy grail”…the long lost pie-fighting scene from The Battle of the Century. Battle is a short comedy from Laurel and Hardy, who officially became a duo in 1927. (Also entering the public domain from 1927 is Laurel and Hardy’s Putting Pants on Philip.) The film holds a Guinness World Record for “the largest number of pies thrown in a custard pie sequence in a movie.” How many pies? 3,000. The novelist Henry Miller remembered it as “the greatest comic film ever made — because it brought the pie-throwing to apotheosis.” For decades, the second reel containing this legendary pie fight was considered lost. Film historian Leonard Maltin called it “a holy grail of comedy” in The New York Times. As described by Neely Tucker on the Library of Congress blog: “It seemed to be a flickering bit of entertainment lost to time, disintegrating film stock and a too-late appreciation of an outdated art form.” Then in 2015 a copy was discovered by Jon Mirsalis, a toxicologist by profession who is also a film collector and silent film accompanist. Mirsalis had obtained a collection of over 2,300 films from the estate of his late friend Gordon Berkow. He spent months making his way through the piles of canisters. When the Battle pie scene shone from his projector, Mirsalis recalls: “I was watching with my jaw hanging open.” While no complete copy of Battle survives, a nearly-complete version of Battle has since been reassembled from various collections, including those at the Library of Congress, MoMA, and UCLA and you can watch it on YouTube here (note the MCMXXVII copyright notice at the beginning). The Library of Congress offers this reflection: “‘Battle’ offers a stark illustration of the detective work (and luck) required to locate and preserve films from the silent era.”

The Tip of the (Melting) Iceberg

Many of the works featured above are famous; that is why we included them. Their copyright holders benefitted from 20 more years of copyright because the works had enduring popularity and were still earning royalties. But when Congress extended the copyright term for works like To The Lighthouse, it also did so for all of the works whose commercial viability had long subsided. For the vast majority—probably 99%—of works from 1927, no copyright holder financially benefited from continued copyright. Yet they remained off limits, for no good reason. (A Congressional Research Service report indicated that only around 2% of copyrights between 55 and 75 years old retain commercial value. After 75 years, that percentage is even lower. Most older works are “orphan works,” where the copyright owner cannot be found at all.)

Now that these works are in the public domain, anyone can make them available to the public. This enables access to our cultural heritage—access to materials that might otherwise be forgotten. As mentioned earlier, 1927 was a long time ago. The majority of works from that year are out of circulation. When they enter the public domain in 2023, anyone can republish or post them online. (Empirical studies have shown that public domain books are less expensive, available in more editions and formats, and more likely to be in print—see here, here, and here.) The works listed above are just the tip of the iceberg. Many more works are waiting to be rediscovered.

Unfortunately, part of this iceberg has already melted. As the story of our silent film heritage shows, the fact that works from 1927 are legally available does not mean they are actually available. After 95 years, many of them are already lost, evidence of what long copyright terms do to the conservation of cultural artifacts. For the material that has survived, however, the long-awaited entry into the public domain is still something to celebrate.

Another part of the iceberg includes works from 1927 and later that may already be in the public domain because the copyright owners did not comply with the “formalities” that used to be necessary for copyright protection. In the past, your work went into the public domain if you did not include a copyright notice—e.g. “Copyright 1927 Virginia Woolf”—when publishing it, or if you did not renew the copyright after 28 years. We know that works published in 1927 and earlier are out of copyright in 2023, but so are works published from 1928-1977 without a copyright notice, works published from 1978-3/1/1989 without a notice and without subsequent registration within five years (the registration fixed the lack of copyright notice), and works published from 1928-1963 with a notice but without a copyright renewal. On our websites for the previous two years, for example, we noted that The General (1926, Buster Keaton) and The Gold Rush (1925, Charlie Chaplin) were already in the public domain due to non-renewal. Current copyright law no longer has these requirements. Even though these works might technically be in the public domain, however, as a practical matter users sometimes have to assume they’re still copyrighted (or risk a lawsuit) because the relevant copyright information is difficult to find—older records can be fragmentary, confused, or lost. That’s why Public Domain Day is so significant. On January 1, 2023, the public will know for sure that all works published in 1927 and earlier are free for use without tedious or inconclusive research to find out if the copyright holder complied with formalities. Still, it is worth shining a light on this “invisible public domain”—including all of the works that entered the public domain years ago due to non-renewal. 8

Oh NO, Canada!

While the US finally turned on the public domain spigot in 2019, after a 20-year drought, Canada’s government has now decided to turn its spigot off. On December 30, 2022, Canada is freezing its public domain for the next 20 years with its C-19 copyright law. Yes, that’s right, Canada is doing the same thing the US did in 1998, with all of the negative effects that have now been well documented.

While the US finally turned on the public domain spigot in 2019, after a 20-year drought, Canada’s government has now decided to turn its spigot off. On December 30, 2022, Canada is freezing its public domain for the next 20 years with its C-19 copyright law. Yes, that’s right, Canada is doing the same thing the US did in 1998, with all of the negative effects that have now been well documented.

The verdict is in: adding an extra 20 years to the US copyright term was a “big mistake.” This is not a quote from someone who is equivocal about copyright; it is a quote from the former head of our Copyright Office. Indeed, there is a consensus among policymakers, economists, and academics that lengthy copyright extensions impose costs that far outweigh their benefits. Why? The benefits are minuscule—economists (including five Nobel laureates) have shown that term extension does not spur additional creativity. At the same time, it causes enormous harm, locking away millions of older works that are no longer generating any revenue for the copyright holders. Films have disintegrated because preservationists can’t digitize them. The works of historians and journalists are incomplete. Artists find their cultural heritage off limits. (See studies like the Hargreaves Review commissioned by the UK government, empirical comparisons of the availability of copyrighted works and public domain works, and economic studies of the effects of copyright.)

So…no one would be silly enough to keep extending copyright, right? Wrong! Incredibly, countries such as Canada are still lengthening their copyright terms—not as a result of reasoned debate, but to comply with trade deals that require harmonization of copyright terms. With harmonization, there is a catch: countries are always made to harmonize with the longer term, never the shorter term, even if the shorter term is a better choice for both economic and policy reasons. Because of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, Canada is expanding its copyright term from an already long life-plus-50 to a longer life-plus-70 years, even though—as Professor Michael Geist explained—the Canadian term extension would “cost Canadian education millions of dollars and would delay works entering the public domain for an entire generation.” Even worse, as Professor Geist writes, the government chose to do so without “mitigation measures to reduce the economic cost and cultural harm that comes from term extension.” Universities, students, teachers, librarians, copyright experts, and even Canada’s own Minister of Justice had recommended a modest registration requirement for the additional 20 years of copyright. This would have given the full copyright term to rights holders who wanted it while allowing works that were no longer being commercially exploited—including orphan works—to enter the public domain. But the government rejected these recommendations.

This is irrational. It would be more efficient to simply levy a new tax on the public and give the proceeds to the small percentage of copyright holders whose works are still making money after a life-plus-50 term. The term extensions not only transfer wealth to a tiny subset of rights owners, but also lock away the remaining works from future creators and the public. Canada is not alone; New Zealand has also agreed to extend its copyright term as a concession in trade agreements, even though this “would cost around $55m [NZ dollars] annually” without “any compelling evidence that it would provide a public benefit,” as pointed out by Michael Wolfe, a former fellow at our Center and expert in copyright policy.

Despite overwhelming evidence that term extension does more harm than good, countries are still extending their copyrights. Even as we celebrate a new crop of public domain works, it is important to realize that the global public domain remains under threat. This makes an understanding of its vital contributions—to creativity, access, education, history—all the more important.

Born in the Public Domain

Composite Image) from NASA and the

Space Telescope Science Institute

In the US, works from 1927 are only entering the public domain after almost a century. But some material is in the public domain from the beginning. This includes ideas, facts, and raw data, which can never be copyrighted. It also includes official works of the US government such as legislation, regulations, legal opinions, hearings, and speeches. As government works, the images from the James Webb telescope, the NASA collections NASA on The Commons (flickr) and NASA image and video library, the famous “Earthrise” photograph taken by astronaut William Anders, and the Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection (a pictorial record of American life from 1935-1944) are all copyright-free! Finally, creators can choose to dedicate their works to the public domain, and many have done so using Creative Commons’ CC0 tool.

What Could Have Been

This site celebrates works from 1927 that are in the public domain after a 95-year copyright term. However, under the laws that were in effect until 1978, thousands of works from 1966 would be entering the public domain this year. Under current copyright terms we will have to wait until 2062. In fact, since copyright used to come in renewable terms of 28 years, and 85% of authors did not renew, 85% of the works from 1994 might be entering the public domain! Imagine what the great libraries of the world—or just internet hobbyists—could do: digitizing those holdings, making them available for education and research, for pleasure and for creative reuse.

Conclusion

Each year, I create this guide to the works that will be entering the US public domain. Each year’s site is a celebration, of course, but it is a bittersweet one. We celebrate the emergence of hundreds of thousands works into the public domain, where everyone can build on them, remake them, present new versions of them, or use them for education or simply enjoyment. The research is complicated and mind-numbingly finicky—and we are lawyers whose professional expertise is copyright and the public domain; further proof of the barriers that poorly chosen copyright regimes can present to those who want to obey the law but cannot easily find out what material is free to use and what is not. A clearer system would benefit us all: artists, citizens and entrepreneurs. But it is not the complexity of the research that provides the bittersweet sentiment; our annual review gets a gratifying degree of attention and a Center for the Study of the Public Domain that was unwilling to…study the public domain would be a strange beast indeed.

The melancholy comes from the unnecessary losses that our current system causes—the vast majority of works that no longer retain commercial value and are not otherwise available, yet we lock them all up to provide exclusivity to a tiny minority. Those works which, remember, constitute part of our collective culture, are simply off limits for use without fear of legal liability. Since most of them are “orphan works” (where the copyright owner cannot be found) we could not get permission from a rights holder even if we wanted to. And many of those works do not survive that long cultural winter. As with the lost silent films I described, all that we have left of them are fragments or stills and some tantalizing contemporary descriptions. Professor Hal Abelson, the MIT computer scientist, once asked: “What does it mean to be human if we don’t have a shared culture? And what does a shared culture mean if you can’t share it?” On Public Domain Day, that act of grateful sharing begins for another year of our culture, something to celebrate indeed. Yet we should also spare a moment to regret that which we have lost.

Want to learn more about the public domain? Here is the legal background on how we got our current copyright terms (including summaries of court cases), why the public domain matters, and answers to Frequently Asked Questions. You can also read James Boyle’s book The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind (Yale University Press, 2008)—naturally, you can read the full text of The Public Domain online at no cost and you are free to copy and redistribute it for non-commercial purposes. For a detailed guide to identifying public domain material, you can purchase Stephen Fishman’s The Public Domain: How to Find & Use Copyright-Free Writings, Music, Art & More. You can also read “In Ambiguous Battle: The Promise (and Pathos) of Public Domain Day,” an article by Center Director Jennifer Jenkins revealing the promise and the limits of various attempts to reverse the erosion of the public domain, and a short article in the Huffington Post, both referring to a previous Public Domain Day.

1 The copyright term for older works is different in other countries. In the EU, works from authors who died in 1952 are going into the public domain in 2023 after a life-plus-70 year term. In the US, only works from 1927 that were 1) published with the authorization of the author or 2) unpublished but properly registered with the Copyright Office in 1927 are entering the public domain in 2023, after a 95-year term. Unpublished works that were not registered with the Copyright Office before 1978 enter the public domain after a life-plus-70 term. In 2023, unpublished works from authors who died in 1952 will therefore go into the public domain. But, because these works were never published, potential users are much less likely to encounter them. In addition, it is difficult to determine whether works were “published” for copyright purposes. Therefore, this site focuses on the thousands of published works that are finally entering the public domain.

2 The 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act gave works published from 1923 through 1977 a 95-year term, expiring on January 1 after the conclusion of the 95th year. Works published before 1978 had to meet certain requirements to be eligible for the 95-year term—they all had to be published with a copyright notice, and works from before 1964 also had to have their copyrights renewed after an initial 28-year term.

The works on our lists are in the public domain because of either a 1927 registration or publication with a 1927 copyright notice. Sometimes there is a 1928 or 1929 registration for a work published in 1927, but this does not prevent copyright from expiring over the original 1927 publication. For most of the featured works we were also able to track down the renewal data indicating that they are still in-copyright through the end of 2022 and affirmatively entering the public domain in 2023.

Foreign works from 1927 were still copyrighted in the US until 2023 if 1) they complied with US notice and renewal formalities, 2) they were published in the US within 30 days of publication abroad, or 3) if neither of these are true, they were still copyrighted in their home country as of 1/1/96. The foreign works on our list met these criteria.

Our site features books, movies, and musical compositions. There are also other creative works entering the public domain, including drawings, paintings, and photography. We have not listed them here because it was more difficult to track down complete copyright information for them.

3 Many sites say that sound recordings from 1923 enter the public domain in 2023—adding 100 years to the date of publication—but these recordings actually go into the public domain on January 1 of the subsequent year, in 2024. Note that the term of protection for sound recordings in other countries is different from the one in the US: in the EU it is 70 years, and elsewhere it is 50 years.

4 There was also rampant exploitation of Black talent: Black musicians, for example, were routinely excluded from copyright’s benefits and denied both recognition and compensation for their work. To learn more about the unequal treatment of Black artists, you can read the excellent scholarship of Professor Kevin J. Greene, including Copyright, Culture & (and) Black Music: A Legacy of Unequal Protection and “Copynorms,” Black Cultural Production, and the Debate over African-American Reparations; Professor Olufunmilayo Arewa, including From J.C. Bach to Hip Hop: Musical Borrowing, Copyright and Cultural Context, Blues Lives: Promise and Perils of Musical Copyright and Writing Rights: Copyright’s Visual Bias and African American Music; and Professor Lateef Mtima, including Intellectual Property, Entrepreneurship and Social Justice: From Swords to Ploughshares.

5 Under the governing copyright law from 1909, the initial term of copyright was 28 years from the “date of first publication” and the relevant publication date was “the earliest date when copies of the first authorized edition were placed on sale, sold, or publicly distributed.” If the copyright was not renewed “within one year prior to the expiration of the original term of copyright” the work went into the public domain at the end of the first 28-year term. According to the 1960 Copyright Law Revision Notice of Copyright Study, date discrepancies are resolved “in favor of the public” and the “term of protection is computed from the earlier date.” The 1960 Copyright Law Revision Copyright Renewal Study adds that “when the copyright notice on a published work contains a date earlier than the year when copyright was actually secured, the first term, and hence the renewal time limits, are computed from the last day of the year in the notice.” With works such as Wings, it is possible that the original film technically went into the public domain in 1955 due to lack of timely renewal, because the renewal was within 28 years of the 1929 registration rather than the 1927 publication.

6 Courts have held that being “nice,” having a “cocky attitude,” and being “young, attractive, and sarcastic” are not independently copyrightable See Shame on You Prods. v. Banks (C.D. Cal. 2015, aff’d 9th Cir. 2017); Campbell v. Walt Disney Co. (N.D. Cal. 2010); Gable v. Nat’l Broad. Co. (C.D. Cal. 2010). You can read the documents from the Enola Holmes litigation here.

7 Endangered film footage goes well beyond the kinds of studio productions are featured here, and includes works of historical value such as newsreels, anthropological and regional films, rare footage documenting daily life for ethnic minorities, and advertising and corporate shorts.

8 Millions of books published from 1927–1963 are actually in the public domain because the copyright owners did not renew the rights. Efforts have been underway to unlock this “secret” public domain, but compiling a definitive list of those titles is a daunting task. The relevant registration and renewal information is in the 450,000-page Catalog of Copyright Entries (“CCE”). Currently there is no way to reliably search the entire CCE, but thankfully, the New York Public Library and others are in the midst of converting the CCE into a machine-searchable format. Even after this is complete, however, confirming that works without apparent renewals are in the public domain involves additional complexities. The HathiTrust Copyright Review Program reports: “Since 2008, over 195 reviewers at 53 institutions have reviewed 900,000 items, determining that more than 509,000 are no longer protected by copyright and have entered the public domain.” These items can therefore be made available online. The work of the New York Public Library, HathiTrust, and other groups continues, with the goal of opening these public domain books to the public.

Written by Jennifer Jenkins. Special thanks to Michael Wright and Grant Young for building this site and to Balfour Smith for researching works from 1927.

Public Domain Day 2023 by Jennifer Jenkins, Director of Duke Law School’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Article source: https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/publicdomainday/2023/

Why celebrate the public domain? When works go into the public domain, they can legally be shared, without permission or fee. That is something Winnie-the-Pooh would appreciate. Community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can perform the music publicly, without paying licensing fees. Online repositories such as the

Why celebrate the public domain? When works go into the public domain, they can legally be shared, without permission or fee. That is something Winnie-the-Pooh would appreciate. Community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can perform the music publicly, without paying licensing fees. Online repositories such as the

The first four films on the list include performances by the great Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, Rudolph Valentino, and Greta Garbo. Moana is a work of docufiction filmed in Samoa by Robert J. Flaherty, who made the famous 1922 film Nanook of the North. Copyright buffs will remember The Cohens and Kellys from the famous copyright case Nichols v. Universal, in which Judge Learned Hand said (among other things) that stock characters are not copyrightable. Faust is a German expressionist take on the eponymous play by Goethe. Because Goethe’s play was in the public domain, the filmmakers were free to reimagine it. And that borrowing went in more than one direction. On the right, you can see one of the scenes in Faust, which inspired the strikingly similar “Night on Bald Mountain” scene from Disney’s Fantasia.

The first four films on the list include performances by the great Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, Rudolph Valentino, and Greta Garbo. Moana is a work of docufiction filmed in Samoa by Robert J. Flaherty, who made the famous 1922 film Nanook of the North. Copyright buffs will remember The Cohens and Kellys from the famous copyright case Nichols v. Universal, in which Judge Learned Hand said (among other things) that stock characters are not copyrightable. Faust is a German expressionist take on the eponymous play by Goethe. Because Goethe’s play was in the public domain, the filmmakers were free to reimagine it. And that borrowing went in more than one direction. On the right, you can see one of the scenes in Faust, which inspired the strikingly similar “Night on Bald Mountain” scene from Disney’s Fantasia.

So . . . No One Would Be Silly Enough to Keep Extending Copyright, Right?

So . . . No One Would Be Silly Enough to Keep Extending Copyright, Right?

It’s a Wonderful Public Domain. . . .

It’s a Wonderful Public Domain. . . .

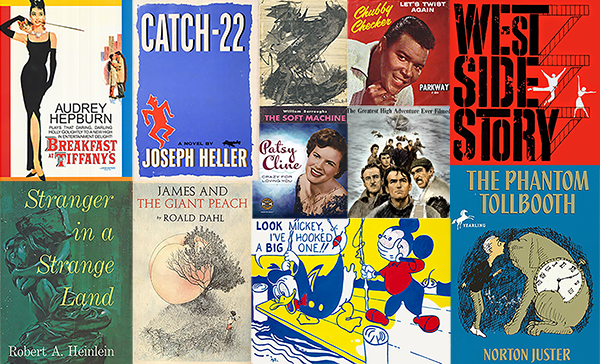

What 1961 music could you have used without fear of a lawsuit? If you wanted to find guitar tabs or sheet music and freely use some of the influential music from 1961, January 1 2018 would have been a rocking day for you under earlier copyright laws. Patsy Cline’s classic

What 1961 music could you have used without fear of a lawsuit? If you wanted to find guitar tabs or sheet music and freely use some of the influential music from 1961, January 1 2018 would have been a rocking day for you under earlier copyright laws. Patsy Cline’s classic